Dabru Emet and the Politics of Shared Texts in Interfaith Dialogue

by Halla Attallah

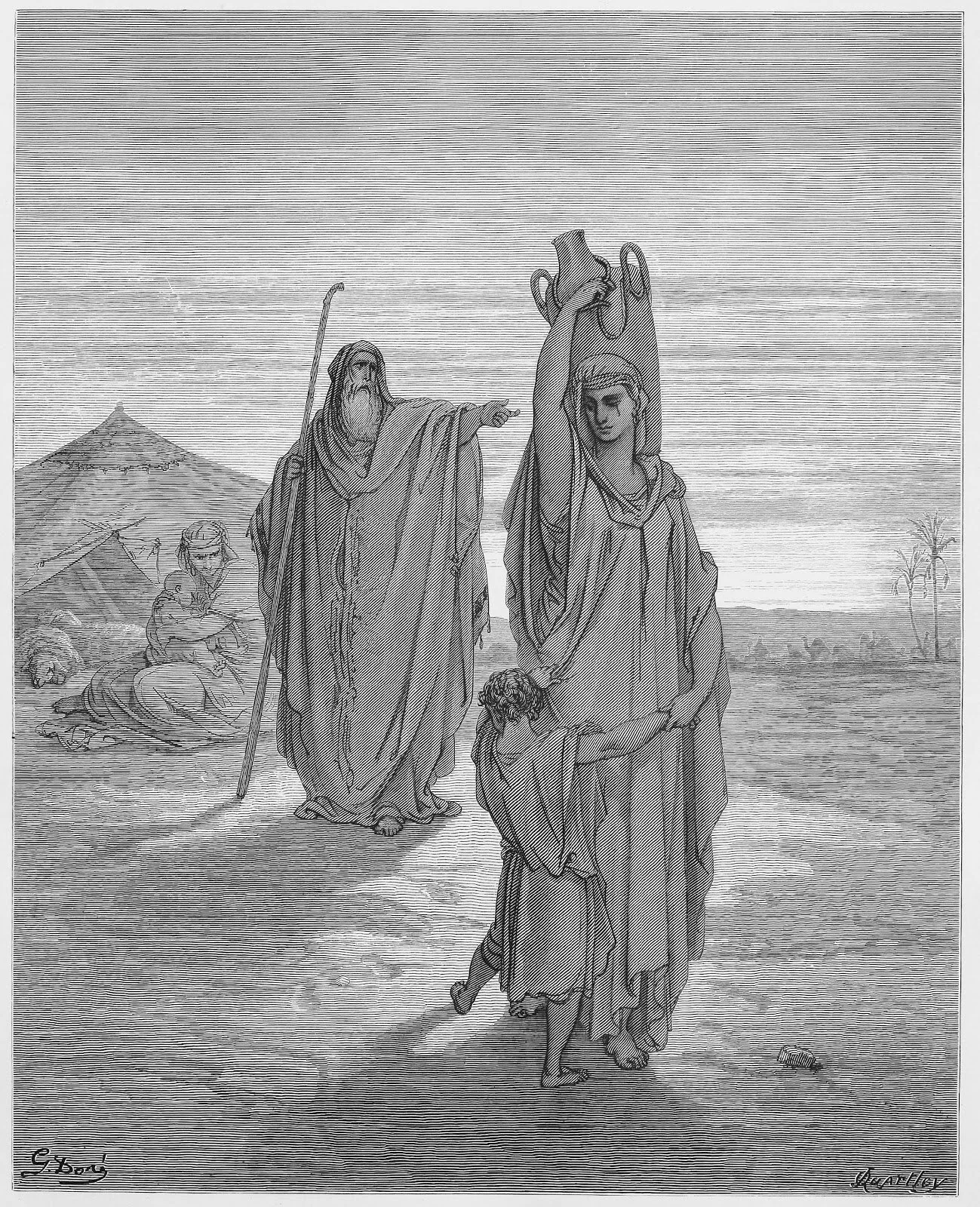

Abraham sends Hagar and Ishmael away

This essay offers a feminist reflection of Dabru Emet’s second claim: “Jews and Christians seek authority from the same book—the Bible”—vis-à-vis the interfaith concept of “the Abrahamic traditions” used in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim conversations. Both models suggest a natural connection based on shared texts, figures, or stories. They also are critiqued for overlooking significant differences, both within and across traditions. Jon D. Levenson, for example, emphasizes that what is understood as the “Bible” and the ways in which authority is derived from it are hardly uniform.

What is of interest to my discussion is that Dabru Emet, like many interfaith efforts, rests on the assumption that similarity is a requisite to dialogue. Without reducing the complexities of interfaith work or mitigating the benefits of accentuating shared values, it is worth reflecting on the implications of privileging similarities as the entry point to understanding. Here, I consider both the limitations and possibilities presented by the notion of a shared text or narrative history. Thinking beyond the parameters of a Jewish–Christian dialogue to include a wider array of faiths and identities, I come to this forum asking who is excluded by the idea of the “same book.” Furthermore, I reflect on how Dabru Emet’s second claim can serve as a valuable paradigm for further discourse that is cognizant of marginalized experiences.

In her essay, “Can Women in Interreligious Dialogue Speak?,” Judith Gruber delineates the ways in which alternative voices are omitted from interreligious conversations. She argues that because “interfaith dialogue takes place at the intersection of male, white and Christian privilege,” essential aspects of female and minority experiences (i.e., differences) are concealed. According to Gruber, female experiences are the objects and not the subjects of interfaith discourse. The issue is not whether women can participate in interfaith conversations. There are many notable female scholars who have contributed in vital ways, including Tikva Frymer-Kensky, one of the authors of Dabru Emet. Rather, the issue is what happens when minority voices introduce perspectives that do not cohere with mainstream readings or already established interfaith frameworks. Can alternative voices participate constructively when speaking from their own positionalities? Simply stated, the issue is introducing different interpretations of the text(s)—shared or otherwise—and bringing different questions to interfaith learning.

Accordingly, it is important to incorporate minority readings of the “same book” emphasized by Dabru Emet, especially when they differ from and even contradict authoritative interpretations. One such valuable resource is the work of womanist biblical scholars. While not directly related to interfaith dialogue, womanist interpretations foreground aspects of the text, including the intricate power structures operating therein, typically ignored by mainstream discourse. Renita Weems, for example, presents a moving reading of the fraught relationship between Sarah and Hagar in her book, Just a Sister Away (1988). Without collapsing our present into the biblical past, Weems draws out the eerie parallels with contemporary female relationships divided by race and class within the United States. Instead of focusing solely on traditional theological questions, such as whether Abraham and his God are truly shared by the monotheistic traditions, womanist scholars broaden this horizon by orienting us toward an intersectionality of experiences that are just as valid and, therefore, essential to a dialogue that is truly inclusive and socially conscious.

Bringing this insight into an imagined Jewish–Muslim dialogue based on the notion of shared narratives, we find that neither textual tradition explicitly questions Hagar’s oppression, namely the use of her body for childbearing without her consent. One could argue that these texts are complicit in her subjugation, just as we, as a society, are complicit in the maltreatment of Black Americans, undocumented immigrants and their children, members of the LGBTQ community, and so forth.

Yet, we also find a sympathetic reading of Hagar that is aware of her oppression and—to some readers—seeks to correct this wrong. In Genesis 16:13, for example, Hagar receives an annunciation directly from God, whom she then names, “El-roi,”—the God of seeing. Hagar is not invisible to God. In Islam, the story of Hagar is not only recounted by the Hadiths—the collected reports attributed to the Prophet Muhammad and his companions—but it also is embodied by Muslims during the Hajj in a ritual known as the Saʿī. Practitioners on foot and wheelchair journey back and forth between the Safa and Marwa mountains in a reenactment of Hagar’s frantic search for water to keep her infant alive. By relying on alternative readings of shared narratives, we theoretically highlight real elements of the traditions absent from mainstream interfaith conversations but meaningful to a wider array of individuals.

Like meeting someone for the first time, initiating conversation with what one has—or appears to have—in common is a valuable and intuitive first step. However, the assumption that similarity is a requisite to dialogue should not be taken for granted. As noted above, the notion of a natural propensity for understanding based on shared texts or narratives marginalizes minority viewpoints within the monotheistic traditions. It also excludes minority religious groups who do not follow a monotheistic or scriptural framework. Interfaith dialogue is not simply a theological conversation between specific groups: it also is an opportunity for self-reflection and an occasion for a deeper societal engagement, especially in a post-COVID-19 world where attention to societal inequalities will become more urgent. We should, therefore, consistently question how similarities are constructed, by whom, and for what purpose. Whose theological and political interests do these similarities serve, and whose do they marginalize? Moving forward, we also should consider how to build on well-established interfaith paradigms—such as Dabru Emet’s second claim—in critical and creative ways. One such approach, briefly explored by this essay, is drawing on alternative voices that foreground different readings of the text. The inclusion of marginal perspectives—not as objects of interfaith dialogue but as active and valued conversation partners—can only benefit and enrich the enterprise of interfaith understanding.

Halla Attallah is a Ph.D. Candidate in Theology and Religious Studies at Georgetown University and served as visiting ICJS Muslim Scholar from 2019-2020.