Globalizing Alabama, Americanizing Jerusalem

by Alana Vincent

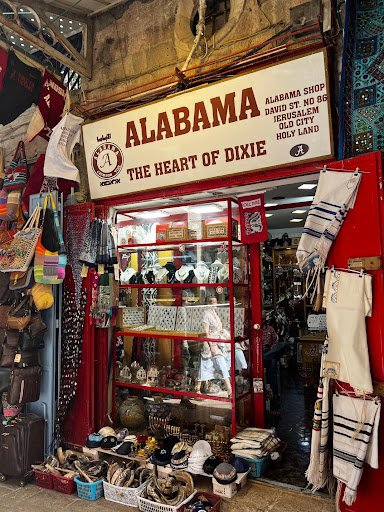

This shop, located a short distance from the forecourt of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, is owned by Hani Imam, a former University of Alabama engineering student. But in spite of the shop’s location, in spite of the fact that the majority of tourists to Israel (55% pre-COVID) are Christian, and in spite of the fact that Imam himself is Muslim, the majority of objects on display almost all appear to be Jewish: everyday items such as kippot, talliot, and jewelry featuring religious symbols such as the Magen David, hamsa, or חַי; objects associated with particular festivals such as pomegranates and shofars for Rosh Hashanah, and menorahs for Hanukkah. Even the items that seem particular to the shop have a markedly “Jewish” flavor—tiles and mugs inscribed with “Roll Tide” feature a transliteration into Hebrew letters; Arabic is much less on display, although the store’s website does feature merchandise with Alabama’s logo flanked by both Hebrew and Arabic transliterations.

Olive Wood Tray With Crimson Tide Ceramic Tile, $50, from Alabama Souvenir Shop.

What is happening here is an eye-catching example of a common phenomenon. The shop is selling specifically to a Christian—and very specifically, an American Christian—public, and what it is selling is not Judaism as such, but rather Jewish ritual objects intended to serve as signifiers of Christian authenticity. Indeed, very similar objects can be found in multiple shops throughout Jerusalem, including the gift shop at the Garden Tomb.

The Garden Tomb is an alternative site of Jesus’s entombment and resurrection, visited almost exclusively by evangelical Christian tour groups. One popular travel guide emphasizes the degree to which the Garden Tomb “conforms to the expectations of simple piety,” noting that “it is much easier to pray here than in the Holy Sepulchre.” However, as the itineraries from leading providers such as Maranatha Tours, Pilgrim Tours, and Holy Land Tours indicate, most tours that include the Garden Tomb will also visit the traditional sites in the Holy Sepulchre, as part of the Via Dolorosa pilgrimage route.

Screenshot of Day 7 of the “Christian Holy Land Guided Israel Tour,” 2023 Itinerary, Maranatha Tours.

Screenshot of “Day 8: Jesus' Steps, Last Days, Way of Suffering, Garden Tomb,” 2023 Itinerary, Steps of Jesus, Paul, & John, 19 Day First Class, Tour & Cruise, Pilgrim Tours.

Screenshot of Day 8 of the “Ten Days Holy Land Tour Travel to Israel,” Holy Land Tours Travel. This tour includes the Holy Sepulchre on Day 7 rather than as an immediate prelude to the Garden Tomb.

Leading field education trips for over ten years, I have learned to expect that students with roots in the more Protestant flavors of Christianity (which are the majority of the students I have worked with from the UK and Sweden) are likely to find the crowds, noise, and general aesthetic of the Holy Sepulchre deeply disturbing and disorienting—not to mention the actual worship practices of the pilgrims whose rites are among those represented in the space. It is not conducive to the quiet contemplation that most such students have learned to associate with prayer or spiritual experience; it does not meet the expectations that they have formed of “the holiest place in Christianity.” It is not at all uncommon for students to experience a spiritual crisis, prompted by the disjunction between their previous understanding of Christianity (as reflected in their own lived identity) and the Christianities they observe in the Holy Sepulchre. Their sense of authenticity—of their own practice being the original, and ideal, form of Christianity—can be threatened.

This is not new; pilgrims from Western Christian backgrounds have long found the prevalence of Eastern Christianities in the site to be alienating, problematic, or even downright threatening. Even as early as the fifteenth century, the Swiss pilgrim Felix Fabri lamented the presence in the Holy Sepulchre of “the obstinate and abominable errors of heathens, heretics, and schismatics.” Fabri wrote less than 200 years after the end of the Crusader period, and much of his commentary is critical of Muslim stewardship over the holy city: the main target of critique was less the behavior of Orthodox and Eastern Rite Christians and more the lack of discrimination exercised by the Sepulchre’s Mamluk stewards. However, by the nineteenth century, tourists to Ottoman Jerusalem such as Clara Waters took equal exception to the rites of the “Greeks and Romish churches,” declaring them “painful for Protestants to see.” American pilgrimage tourism, in particular, was predicated upon the idea of the exact sites of biblical events as a form of proof-text, an empirical demonstration of the reliability of scripture, and the sense of religious alienation produced by the Holy Sepulchre was therefore particularly (albeit by no means uniquely) problematic for American pilgrim-tourists. It was against this backdrop that criticism of the accuracy of the Holy Sepulchre site gained currency, and arguments for the Garden Tomb as an alternate site of devotion gained prominence.

Landscape and archaeological sites were not the only features of Jerusalem which American Protestant pilgrim tourists saw as empirical proof of their biblical faith. People were also an important proof text. Prior to the twentieth century, Jews in the Holy Land were a “witness people,” whose “primitive” and impoverished condition attested to their error in rejecting Christ, while simultaneously their continued existence attested to God’s grace. The presence of Jews in Jerusalem, specifically, served as a harbinger of end times prophecy, which dictated the return of Jews to the promised land prior to Christ’s return. Their devotional practices—particularly their prayers at the Western Wall—were no less foreign to Protestant visitors than those practiced in the Holy Sepulchre. But where Eastern Christianities challenged understandings of Christianity as a universal religion, Jewish practices were already accounted for as superseded. The “Wailing Wall” was thus able to serve as both a living tradition which confirmed the general accuracy of the “scientific” account of biblical sites and as confirmation of the current abjection of the Jews.

The establishment of the state of Israel and the consequent alteration in the status of Jews in the twentieth century did not prompt a similar alteration in the way that American Protestant pilgrim tourists view Jews and Judaism, save, perhaps, to lend further credence to apocalyptic interpretations of history. At the same time, a range of factors—from an increased emphasis on individualized forms of spirituality (“seeker” culture) to a move to recover the “authentic” practices of the early Church—produced a heightened fascination with Jewish ritual life not just as a prooftext for the truth of scripture but also as a potential resource for Christian spirituality.

This, then, accounts for the particular souvenir offerings on display at the Alabama Shop. Unlike the gift shop at the Garden Tomb, whose stock is very clearly aimed at self-identified “Messianic Jews” and intended for use (study texts, educational models, and mezuzot bearing the Messianic/Christian Zionist symbol of an ichthus and menorah joined by a Star of David), the Alabama Shop’s inventory is primarily items intended for display. The clear exceptions to this are the talliot and shofars, whose use in evangelical communities is well documented, and the kippot, which are likely to be used at least on a visit to the Western Wall.

“Mezuzot” with Christian symbolism sold at the Garden Tomb gift shop (as well as other similar shops). Photograph by the author.

To say that an item is intended for display, rather than use, is not to say that it does not have a function. Even the most mundane decorative object plays a role in the curation of its owners’ self-presentation. Souvenirs are an especially potent form of self-display, and religious souvenirs hold a particularly high degree of symbolic value—which, at the point of sale, translates into exchange value. The items on display at the Alabama shop are carefully curated to appeal to its primary audience precisely because of their display function: they signify a connection to the “religion of Jesus” as attested in scripture without necessarily obligating their purchasers to any particular ritual practice.

While sound demographic data on the religious affiliation of college football fans doesn’t exist, it is worth noting that Evangelical Protestantism is by far the dominant religion in Alabama. In fact, there is a strong correlation between the states where evangelical Christianity dominates the religious landscape and the states where the Southeastern Conference (SEC) dominates sports fandom. Florida is the outlier—there, evangelicals and the religiously unaffiliated both constitute 24% of the population; in every other state in the SEC, evangelicals are the largest single religious group, and usually by a healthy margin. (The mean difference between Evangelical Protestantism and the next largest religious group in the SEC states, including Florida, is 19.5%.)

So while not every evangelical tour that comes to Jerusalem will pass by the shop, and not every evangelical tourist will have strong associations with SEC football—much less Alabama football—the odds are broadly in Imam’s favor. Enough of the tourists that pass by will be American, and enough of those will, even if they are not themselves members of the Crimson Tide community of worship, find its cultural references familiar and comforting. For these pilgrim tourists, the familiarity of the logo and slogan on the shop sign is a powerful antidote to any sense of estrangement they may have experienced in the Holy Sepulchre. The particular items displayed beneath the sign continue the same work of corroborating the target audience’s understanding of religious authenticity and reassuring them of their cultural and spiritual belonging in the Holy Land.

Alana M. Vincent is Associate Professor of History of Religions at Umeå University. Her work focusses on the shifting boundaries between Judaism and Christianity in religion, literature, and popular culture. She can be found at @amv@religion.masto.host and, less frequently, on Twitter as @ProfAMV.