A Study of American Kokutai

by Jolyon Baraka Thomas

About a year ago, a colleague tweeted that he had recently read my Faking Liberties with his grad students at a Japanese university. “We joked that a good subtitle might be ‘A Critique of the American Kokutai’” he said, referring to the wartime-era word for Japan’s unique body politic.

Often translated as “national essence,” kokutai literally means “nation-body.” In prewar and wartime Japan, propagandists and the Japanese Ministry of Education used the term to indicate the sacralized yet secular polity, an entity imbued with the numinous qualities of divinity but grounded in the practical realities of governance. According to kokutai ideologues, the Japanese nation was a peerless land ruled over by a heaven-descended god-kings. It had no earthly equal.

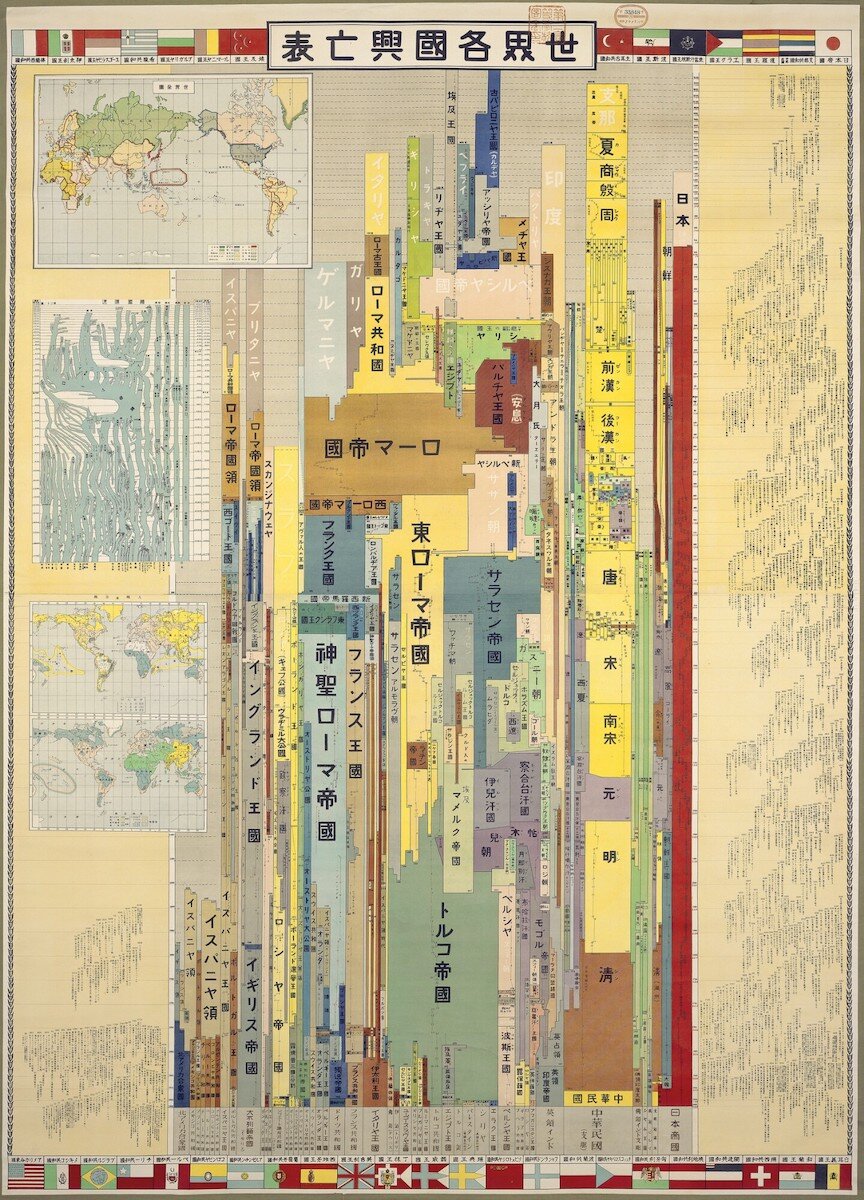

This 1926 Japanese infographic depicts the “Rise and Fall of the Nations of the World.” Japan’s monarchy is depicted in red on the far right, dating back 2600 years to the “age of the gods.” The image reflects the conceit that while some nations like China may be older, Japan alone boasts an unbroken imperial line. (By contrast, the United States is depicted at the far bottom left in indigo, a rank beginner in the global game of empire.) The smaller flow chart (top left, below the political map of the globe) depicts the “Origins of the Various Nations,” again reinforcing the sui generis quality of the Japanese polity. The two maps immediately below depict the races (top) and religions (bottom) of the world. Thanks to David Fedman @dfedman for bringing this graphic to my attention.

Since Japan’s defeat in 1945, scholars have regarded the kokutai concept critically, even dismissively. But strikingly, they have generally accepted the underlying assertion of Japanese uniqueness. That is, if during the war kokutai meant that Japan had a divine mission to rule the whole world, after the war the concept served as proof that Japanese leaders had fused religion with politics in a particularly egregious fashion. As exemplified by the pejorative phrase “State Shintō,” imperial Japan became the paradigmatic model of “bad secularism.”

This clip from Frank Capra’s 1945 propaganda film Know Your Enemy: Japan depicts the Japanese as slavishly devoted to a false god-king while simultaneously equating the US polity with Christianity.

Newsmap: End of a Myth. This infographic for members of the US armed forces narrates the most radical changes introduced by the American-led occupiers in the first few months of the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945–1952). The occupiers focused specifically on repudiating the claims that Japan’s emperor was divine and that the nation was destined to rule the world. Reforms of the public school curriculum were central to this project.

But was Japan really so unusual? Scholars of religion might learn a great deal if we redeployed kokutai as an analytic term, stripping it of its putative Japaneseness and applying it to other countries, including the United States: How is the American national body constituted? What are its claims and aims? What notions of territory, mission, and membership does it presuppose?

Answers to these questions can be found in concepts like the doctrine of discovery, manifest destiny, the city on a hill, or moral arcs bending toward justice. They can also be found in Healan Gaston’s magisterial history of “Judeo-Christian” rhetoric in the United States. As she persuasively demonstrates, exceptionalists have used “Judeo-Christian” to assert civilizational superiority, treating the United States as a divinely inspired nation without peer. By contrast, pluralists have used “Judeo-Christian” to highlight tolerance and inclusion. Both have used the phrase to signal a uniquely American orientation that makes us good, perhaps even the best. “Judeo-Christian” is the American kokutai.

I am particularly keen on theorizing from Japan in my publications, but I know that not everyone will be immediately convinced that the kokutai concept can be fruitfully applied to the United States. Nevertheless, I think that the historical parallels are worth investigating, especially because influential theories about American uniqueness emerged in response to the specter of Japanese totalitarianism. Japan may only appear on four pages of Gaston’s book, but the resonances are far deeper than this sparse representation would suggest.

For example, Japanese officials began deploying kokutai propaganda as a bulwark against “individualism” in the 1930s. This was precisely the moment when a personalist “Judeo-Christian tradition” appeared in American discourse as a counter to “totalitarianism” (Gaston, chapter 3). Although the claims had different flavors, they featured the same ingredients: individual and collective, religious heritage and political solidarity, national morals and global mission.

Gaston’s chapter 8, “Judeo-Christian Visions under Fire,” provides another fruitful example that particularly caught my attention. As part of my broader argument that prewar Japan was characterized by a secularist system rather than a national religion, in Faking Liberties I had chided Robert Bellah for his term “civil religion” (30-32). Bellah’s functionalist concept was too clumsy for the critical analysis of secularism I wanted to conduct. Moreover, his claim that “civil religion” should not be mistaken for an “American Shintō” seemed to protest too much. By contrasting American “civil religion” with Japanese “State Shintō,” wasn’t Bellah problematically arrogating to himself the right to judge whose religion could count as wholesome, good, and just?

I didn’t know until I read Imagining Judeo-Christian America that Bellah was responding to Harvey Cox with that throwaway line about Shintō, nor had I considered that both were participating in a longer conversation that included Will Herberg and Martin Marty. Due to my own training, I had just assumed that Bellah was thinking about the United States through the lens of Japan.

Gaston’s account prompted me to review Bellah’s rumination on the afterlife of his 1967 civil religion essay in the second edition of The Broken Covenant. There, Bellah confirmed that conversations with Japanese colleagues had prompted him to develop the idea, but he also lamented how many of his American colleagues conflated civil religion with what he called “the idolatrous worship of the state,” a “perversion” of the “central and normative tradition.” The language is revealing. It shows that civil religion, like kokutai, was always intended to prescribe normative attitudes and behavior, not just describe a historical tendency or sociological reality. This is the “slippage” between is and ought that Gaston so eloquently describes (2).

Recently, many scholars have been tempted to turn to the concept of civil religion to explain both the rituals and rhetoric of the Capitol attackers and the pomp and circumstance attending Joe Biden’s inauguration. But at a time of questionable claims that the United States is the “greatest country on earth” and specious assertions that recent domestic violence is “not who we are,” it seems particularly fitting to apply the exceptionalist rhetoric of another country to the United States. Redeployed in a re-descriptive register, the kokutai concept can help us clarify moments past and present when Americans like Bellah made theological claims about our collective missions and shared moral orientations. Just as kokutai took on a new cast after Japan’s stunning military defeat, some of America’s “kokutai orthodoxy,” including the concept of civil religion, will necessarily look different with the benefit of historical hindsight.

Imagining Judeo-Christian America envisions the American kokutai in just this fashion. It investigates the multifarious ways that various parties dreamed America into being with the aid of empirically unverifiable claims about divine mandates and shared values. It shows that assertions of national uniqueness are often specious, even as it proves that they are particularly tenacious. It is a book we must all read, for it does not merely imagine America. It describes all secularist worlds.

Jolyon Baraka Thomas is assistant professor and interim graduate chair in the department of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of Drawing on Tradition: Manga, Anime, and Religion in Contemporary Japan (University of Hawaii Press, 2012) and Faking Liberties: Religious Freedom in American-Occupied Japan (University of Chicago Press, 2019). He is currently working on a third book titled Difficult Subjects: Religion and the Politics of Public Schooling in Japan and the United States (under contract with University of Chicago Press).